A Cable Snaps

October 28, 2009

“War is so unjust and ugly that all who wage it must try to stifle the voice of conscience within themselves.” —Leo Tolstoy

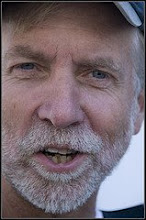

THE DOORMAN wheels two suitcases through the front door of the Hotel W and toward my waiting cab. Walking beside him is a handsome white guy, mid-forty-ish, lanky and fit-looking and with a bit of a tan. The two of them are chatting, smiling, and I imagine my new fare as a golf or a tennis pro, or maybe he once played college shortstop somewhere in Iowa or Nebraska or Oklahoma. While I stow his luggage and he tips the doorman I note with envy his full head of hair, about an inch-and-a-half long, buzz-cut, and gone bone-white well before its time.

“Headed to SFO,” he says, as we pull away from the curb.

Forty bucks. “Music…,” I say, “to a cab driver’s ear.”

He gives me my hoped-for chuckle, and says, “You gotta make some money.”

“Where are you flying to today?” I ask.

“Denver,” he says. “Tomorrow it’s Dubai and Kandahar.”

“Kandahar… What’s your work?”

“I work for a private security contractor. Excuse me…,” he says. “Hello…?” In the rearview I see him holding a cell phone to his ear. “Yes, I need to check Frontier Airlines flight number…”

Last night I read a long article at Counterpunch.org in which the private security industry is portrayed as teeming with ex-military and ex-CIA officers earning thrice their previous salaries, thanks to inflated, insider, government contracts. By the time my fare snaps his phone shut we’ve passed the Moscone Convention Center and are rolling toward the Whole Foods Market on Fourth Street. I ask, “What’s your function in the security industry?”

“I’m a recruiter.” He chuckles again. “I hire mercenaries, you would say.”

I like to think of my cab as a sanctuary. In my cab you’re safe, you’re all right, even if you’re a prostitute (my first fare, 25 years ago, was a 4 a.m. street-walker and I was glad to have her) or a drug dealer (as long as you keep your heat stashed) or a preacher (your religion) or a drunk (the contents of your stomach). My job is not to judge you but deliver you safely from Point A to B.

“You folks have been getting a lot of flak lately.”

“A lot of things get exaggerated,” he says.

“What kind of things?”

“When you are fired on in the course of your duties, you have a right to fire back. To do whatever you have to do to save your own life.”

“Iraq…?” I say. “That Blackwater convoy in Iraq?”

“Yes,” he says. “I’m a recruiter for Blackwater. That whole thing really got exaggerated.”

In September 2007 a convoy of US diplomats was toodling through Bagdhah when their Blackwater escorts—private security contractors, mercenaries you would say—suddenly opened fire and exaggerated seventeen Iraqi civilians into bullet-riddled corpses. The new Iraqi government demanded the entire company leave the country, and perhaps a few low-level personnel did go home and start flipping burgers, but Blackwater itself simply took a new name—“Xe”—and went right on chugging.

“You guys changed your name,” I say. “Now you’re… She?”

My fare says, “Zie”—it rhymes with lie and die—but during the rest of the ride he uses only Blackwater.

As we climb the ramp to 101 South, I see a row of parked, black-and-white police cruisers blocking all lanes heading in the opposite direction. Earlier this week our Bay Area “Indian summer” was interrupted by winds gusting to 50 miles an hour. An overhead cable on the Bay Bridge snapped and 5,000 pounds of construction debris rained down on rush hour traffic. Miraculously, no one was seriously injured, but now the bridge is closed indefinitely.

“I’m really glad to have you in my cab,” I tell my fare. I swivel my head, make quick eye contact—men’s magazine ad directors could use this man as a model, portraying success, confidence, The Smart Money—and turn my eyes back to the road. “Our politics are going to be very different, but I’d really like it if I could ask you some questions.”

“Absolutely!” he says.

“This idea of sending contractors, profit-making companies, to fight our wars… I don’t see how this can possibly work out well?” Not exactly a question…

But he doesn’t mind: “When we go to war, it should of course—of course—be the military that moves in to pacify things, establish the tone.” He sounds practiced, smooth; his duties must include some public relations. “But when the military has stabilized a situation, the private sector can do a much better job at many aspects. And do them cheaper. We’re cost-effective. We’re a good deal for the taxpayer.”

I say, “Soldiers in the military want to go in, do the job, and go home. Profit-making entities have an entirely different motive.”

He’s ready: “The private sector can serve as a ‘force multiplier.’ The fewer troops Obama sends in, the happier he and the taxpayer are going to be. Obama will be using us more and more,” he says. “You’ll see.”

We’ve just passed Candlestick Park, where a week from Sunday 50,000 people will gather to exhort the San Francisco 49ers and Tennessee Titans to knock each other senseless. I think: Blackwater and Obama now seeing eye-to-eye—not reassuring.

My fare continues: “The private sector can do things the military isn’t set up for. Who do you think cleaned up the Deck of Cards?” Early in the Iraq invasion, American intelligence groups printed up a deck of playing cards featuring the names and faces of fifty-two “most-wanted” Iraqis. “Contractors,” he says. “That was contractors working with Special Ops forces.”

I say, “The same people who brought us Abu Ghraib, rendition flights, secret prisons, torture, a ruined global reputation. A hundred people have been killed in our custody.”

We’ve hit the long flat straightaway heading toward South San Francisco, a sixty-five mph zone. It feels like we’re doing about a hundred and ten, but I look down at the digital speedometer: 58. To our left, I see that the winds have riled up the bay. Usually the water here is steely-blue and calm, but today it’s milk-chocolate colored and choppy, dancing with millions of short, triangular, white-tipped waves: now-you-see-em, now-you-don’t traffic cones.

My fare: “Have you heard of waterboarding?”

“Well, yes…” Who hasn’t?

He asks, “Have you ever been waterboarded?”

“I’ve seen live demonstrations, I’ve seen people waterboarded on youtube, I’ve watched the debates in Congress…”

“Do you think waterboarding is torture?”

“I’ll go with John McCain on that one.”

“I’ve been waterboarded,” my fare says. “It didn’t kill me. It was part of a training program…”

“I know about SERE.”

“If waterboarding was torture, do you think we’d have been trained with it?”

“Did you know the people doing it?”

“Yes.”

“Did you know it was going to end, and that you’d all be friends again?”

“Yes.”

I ask, “How many times were you waterboarded?”

“If you’ve been waterboarded even once, you know it won’t kill you. You’ll survive. It’s not that serious.”

“We tried Japanese as war criminals for waterboarding. It’s illegal—it’s against our laws, it’s against our treaties. I’m not someone who actually thinks the Constitution is just a goddamned piece of paper!”

Eye contact can damp down a convsersation, but in my cab—with the passenger staring at the back of my head, with me watching the road, with the presumption of anonymity, and with a guaranteed end not far ahead—a freewheeling intimacy often takes hold.

My fare asks me, “Have you ever been out of the country?”

Oh, boy—now I’m ready: “I was in Kandahar in 1974.” My fare was not expecting this answer, nor the bonus, the unspoken Sonnyboy! that comes along with it. There follows a micro-silence, a tiny hole in the offensive line of this conversation, and now I'm through it, into the backfield, off and running: “I’ve visited all fifty states, I’ve circled the world four times with my backpack—forty-some countries. I spent a month in Afghanistan in 1974 before people started destroying it. My father was in the OSS during World War II and spent 33 years in the CIA. I grew up in a neighborhood where maybe ten percent of the adults worked for the CIA, all of them incensed about communists torturing and killing people in a secret gulag in Siberia. They’d be puking their guts if they knew the CIA—and their force multipliers—had built a global secret prison system where one hundred people have died from our torture.”

“Where’s the evidence?”

“I don’t have it with me, but it’s certainly out there.”

“Where?”

“Seymour Hersch—reported the Mai Lai massacre—now he says a hundred people have died in US custody.”

“I don’t believe it,” my fare says. “I’ve got to see the evidence.”

“You can ignore it if you want, but it’s there, and it’s credible. Are you aware of the reporting?”

“You can find a lot of reporting,” he says. “I imagine you’re a New York Times reader. I read the Wall Street Journal.”

“Are you aware of the reporting or are you not aware of the reporting?”

I was five years old when my parents took me and my siblings to a multi-family Easter egg hunt at Dumbarton Oaks in the Georgetown section of Washington DC. My parents had never cut my two-year-old brother’s hair, and now Scott had gorgeous, silky, shoulder-length locks. Another boy, my own age, kept saying that Scott was a girl, and I warned this boy that if he kept on saying it, I was going to have to hit him. A moment later my father came trotting around the nearby hedge to investigate the commotion. I remember hearing my name called, remember pausing from my business-like pummeling of the other kid, remember looking up and seeing Dad’s big, amused, approving, rarely-granted smile.

My fare: “Have people died in our custody? Sure they have. Have Americans died in custody in prisons here in the US? Sure they have. And something like… twenty-nine thousand Americans die in traffic accidents each year? Why aren’t there big billboards tracking that figure? But five brave boys died in Afghanistan yesterday and nobody can stand it…”

I interrupt him: “Excuse me… I have to say that I find this conversation obscene. How’d we get to where we’re using traffic deaths to justify waterboarding, torture, murdering people in secret pr…?”

He interrupts right back: “This didn’t start with Afghanistan or Iraq. I spent twenty years in the military. What do you think your father’s people were doing? The CIA’s been rigging elections and assasinating people since the day it was born.”

No one can win these arguments—they’re circular, pointless, polarizing, and even well-rehearsed—but they’re impossible to resist, and oh so seductive. “These torture prisons are brand new,” I say. “And in the fifties and sixties no one worked at the CIA just to get a big fat Rolodex so they could quit and open private security firms.”

He says, “You ignore the fact that for you and me to be having this conversation lots of Americans have had to put their lives, their bodies, on the line.”

“I didn’t ask,” I tell him, “and the taxpayer didn’t ask, to have anyone tortured so that you and I can have an obscene conversation.”

I hear him sigh. “You’re a world traveler. And that’s great. You’re obviously an educated person. A lot of this is a matter of perspective…”

I can find comforting ways to rationalize many of my own screwups, even a couple of the most egregious ones, but some things are flatly indefensible. And this matter of casually torturing thousands of people…in the name of national security…at the curl of a vice-president’s upper lip… Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that America—all of us—will pay for this, and pay big. I tell him, “I’m never coming over to your perspective.”

As we glide up the ramp to SFO, we go quiet, our first silence since my fare closed up his phone. I believe in the maxim, What we resist, we become. And this is not the first time that I, while resisting the arrogance and self-righteousness of those who champion recreational torture and optional wars as a patriotic strategy for protecting American family values—phwew, there's a mouthful—have certainly registered my own self-righteous arrogance. No matter. Lines do exist. Torture is wrong, evil. And I don’t want this man thinking that he or any of his war criminal cohorts will be coming home to some sort of hero’s welcome, to some sort of sanctuary.

As I pull to a stop at the Frontier gate, he summons a hearty, same-team, bygones-be-bygones voice. “So… what do I owe you?” The unspoken bonus: My friend.

“Nothing.” Red digital figures—$33.25—glow from the meter. I punch a few buttons and it goes dark.

“Aw, man,” he says. The PR voice is gone. “Come on. Take my money.”

“I won’t touch it.”

I’m out of the cab. I’m at the back, opening the hatch. I set his first bag down at the curb. He’s out of the cab, too—I see his brown shoes come to a stop next to his suitcase—but I won’t look up at him. I keep my eyes on the asphalt of the roadway, the curbside concrete, the green rear bumper of my cab. In my peripheral view I note that my fare’s hands are extended out to his sides, palms up, like the poor, wired-up guy perched up on the box at Abu Ghraib, with the smock and that pointy black hood over his head. I hear my fare’s plaintive voice: “Don’t be like this…”

Anyone near us on the sidewalk would think, Why are these cab drivers always so pissed off? Look at that idiot giving shit to the nice-looking businessman…

I place his second bag on the sidewalk.

“Come on, man. Take the money…”

I close the hatch, turn toward him, square up, and finally look him in the eye. “Give it to some starving kid in Afghanistan.”

“Fair enough.” He sounds relieved, exonerated. He shoots his right hand toward me, waist high, looking for me to shake it.