'Nam Vet

Memorial Day -- 2006

9:18 a.m. - - Post and Mason (in front of Morton’s Steakhouse, half a block from Union Square)

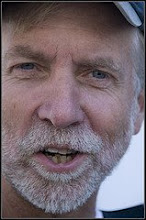

HE’S A SHORTISH 56-YEAR OLD WHITE GUY, wearing blue jeans, a plaid long-sleeve shirt, and a light brown baseball cap pulled down low -- I never do get a look at his eyes.

“I’m going to Sutter and Hyde – Aces. ("Aces" is a bar between the Tenderloin and Polk Gulch.) I’m going to raise a toast before all the other crazies come out. I think I’ve got the jump on most of ‘em.”

This morning the city’s hotels are full of Memorial Day Weekend tourists plus 11,000 Physician Assistants attending a three-day meeting at Moscone, but they’re all slow risers. So far I’ve had only two rides, one of them a man named Ernesto who arrived in the States from Peru just three months ago, and whom I coaxed from a bus stop with the offer, in Spanish, of a free ride. (“Seguro?” he asked before getting in. For real?)

So I’m glad to have my current fare, a real-live paying customer. “Were you in the service?” I ask him.

“Army. Drafted. They sent me to Vietnam in 1969 when I was nineteen years old. I’d already been accepted at Berkeley but I didn’t want to go to college yet and so I took my chances -- almost the biggest mistake of my life. They drafted me right away. This was before the lottery, but it wouldn’t have mattered… In the lottery I came up number 36.”

In the middle of the Vietnam War, in order to address the embarrassing fact that it was almost exclusively the poor and the black who were being shipped off to become the maimed and the dead, the United States Selective Service Administration held a nationally televised lottery. Three hundred and sixty-five ping pong balls, each labeled with a different date of the year, were placed in a hopper and drawn out one by one. All males of draft age -- eighteen to twenty-six years old -- were assigned a draft number corresponding to the order of the draw. If your birthday was written on the first ping pong ball drawn, you were #1. If your birthday was written on the second ping pong ball, you were #2. And so on... Everyone who received a number lower than 60 was immediately sent a draft notice. Anyone with a number of 150 or higher was considered virtually “draft-proof” -- and those in the middle had to sweat it out.

My birthday, September 15, was written on the two-hundred-and-ninety-first ping pong ball to be drawn, and at the age of 18 I had the luxury of knowing that I would, almost certainly, never have to serve in the military if I didn’t want to. And although I sometimes try, I can’t even imagine the life I’d have had if I’d been sent to Vietnam.

“We’re you infantry?” I ask.

“Infantry,” he grunts.

“Shooting at people? Bullets whizzing by your head...?”

“I was shooting at them, they were shooting at me," he says. "We'd be in the field 45 days straight, lay low for seven, get resupplied by air, then go out for another 45 straight. But it was better than this Iraq war. These poor kids riding around in the desert in armored vehicles waiting for someone to shoot at them or some roadside bomb to blow them up. At least in the jungle we knew what to do: Hit ‘em -- before they hit you!

“I was in ‘Nam for twelve months and 26 days. Twelve months was a complete tour, but I gambled again. If you were already accepted to college, and if you had less than six months to go when you finished your tour, they would cut you loose. They didn’t want to ship you back stateside, give you a month of R & R, train you in a new job, and then lose you after maybe a month or two. So I stayed an extra 26 days in ‘Nam, and when I got out I had less than six months in my hitch, so I was done. It worked out -- I was able to go to UC-Berkeley, buy my first house... I knew lots of people who didn’t make it back, and I’m sorry about that. Better them than me, I say, but I’m going to raise a toast for all of them today.”

We’re stopped in front of Aces now. It’s been a short ride -- three minutes. I kill the $5.10 on the meter and say, “I can’t take your money today.”

He’s been matter-of-fact all along. No self-pitying lamentations, just straight-shooter reporting. But suddenly he erupts. His voice jumps twenty or thirty decibels, from quiet murmur to heavy mortar fire. He jumps forward and I feel the weight of his body shudder my seatback. “There’s no way, man!" he screams. "No way!” He swings his right arm toward me and his open hand slaps against my right shoulder, hard. “You’ve got to pay your gate, man -- no way!”

He’s got some bills folded up in his other hand. He pushes them toward me, and I take them and I thank him. He’s a ‘Nam vet, and he’s certainly earned the right to have things any way he wants them on Memorial Day.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home