COINCIDENCE!

FLASHBACK: May 1984

A quarter-century ago...

I was standing by the side of a two-lane highway in the Japanese countryside, a full day’s hitchhike west of Kyoto, and holding up a cardboard sign onto which I had inked the Japanese characters for “Hiroi" (broad) and "Shima" (island). It was dusk and I was still a long way from Hiroshima, and it was just starting to rain. In my book All the Right Places I wrote about what happened next:

An enormous silver tanker truck with a Mobil Oil logo on the side slowed to a stop right next to me. The driver smiled and nodded me up into the cab. He was perhaps the friendliest-looking person I’ve ever seen, one of those rare gentle people who seem not to have a mean or aggressive vein in their entire being. A white sports shirt and tan skin gave him the relaxed air of a cruise ship tennis pro. Of all the Japanese I met, this man, with lean face, high cheekbones, bright, perfect teeth, round eyes, and no glasses, would be the country’s best representative…

We knew only a few words of one another’s language, but we used them at lot. I was able to determine that he had two jobs; for every 10 days he worked for ‘Mobil Company,’ he also served five in the navy. West of Hiroshima, the Japanese Navy and US Marines share an air station, at Iwakuni, and after delivering his load of gasoline to the Hiroshima airport, the driver would report for duty. He was thirty-two -- my own age -- married, with a girl, ten, and a boy, seven. He lived in Tokyo and his name was Kanemoto. Kanemoto said we would cover the 97 kilometers to Hiroshima in two hours.

And we did. While a torrential rain lashed the truck, I sat high up in the cab, warm and dry, using my guidebook Japanese and plenty of hand gestures to trade stories with Kanemoto. He drove me all the way to Hiroshima and veered out of his way, maneuvering his giant truck down small side-streets, to drop me as close as possible to my chosen hostel. (Chapter 18 of All the Right Places is a full, four-page account of our ride.)

FAST FORWARD: March 2009

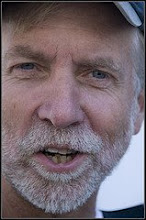

I’m 58, a seasoned professional driver myself now, and one day I receive an e-mail with the subject line, “COINCIDENCE!”

The writer tells me his name is Rick Wilson. Rick is 35 years old, and a native of New Zealand. He is married to a Japanese woman, and now the two of them are living in Hong Kong, where Rick teaches English as a second language.

Rick tells me that he recently asked some friends in Hong Kong where he might find some travel memoirs written in English, and they directed him to a particular library along a particular Hong Kong subway route, where he came across a copy of All the Right Places. “Imagine my surprise when I read on pages 82/83 about an amazingly friendly and gentle MOBIL company driver named Kanemoto. SOUNDS LIKE MY FATHER-IN-LAW!!!! My wife Maho rang Japan and spoke to Kanemoto (her father)!!!! He remembers you well and it made his day.”

Over the next few weeks Rick and Kanemoto and I exchange letters expressing our astonishment and delight, and we also exhange gifts –- I send them copies of my book, and Kanemoto sends me a beautiful silk scarf and two exquisite tapestries which now grace the wall of my studio (I see them as I type this).

TODAY: Wednesday, September 23, 2009

At noon I park my taxi near Pier 33, from where tours to Alcatraz Island are launched, to have a cup of coffee with Rick's parents, Eva and Bill, who are visiting San Francisco. Rick's whole family, including Kanemoto, is getting as big a kick as I am out of this small-small-world connection -- 25 years down the long twisty road. And today Rick's mom shares another interesting twist: “When Rick first showed his wife, Maho, what you had written in your book, Maho telephoned her father in Japan and asked him, 'Did you pick up a gaijin (foreigner) hitchhiker on your way to Hiroshima in1984?' And Kanemoto-San, said, ‘How did you know? I never picked up a single hitchhiker before that, and I never picked up a single hitchhiker after that. Just the one. How did you know?’ He couldn't believe it when Maho told him she'd read about it in a book! At what makes it even more interesting is that it was absolutely against the company's rules for Kanemoto to pick up hitchhikers -- and Kanemoto is a rule-conscious, straight-laced guy.”

Rick’s dad, Bill, laughs: “Until we’ve all had a couple of beers!”

We sit in the Pier 33 café, a scoured blue sky overhead, and talk about our lives. Bill and Eva both grew up in New Zealand, met when they were quite young, married when they were 21, and have raised two sons. I ask what kind of work Bill and Eva do, and Eva says she used to work in a law office where Bill had once been a lawyer. I ask Bill if he is still a lawyer, and he says he is a judge now. I ask how judgeships work in New Zealand, and he says there are four levels of judgeship. I ask which level is he? Bill says, "I'm a Supreme Court justice now..."

We pass a raucous hour together, and by the time they go off to their Alcatraz tour and I head off for the last couple of hours of my shift, I'm buzzing like a cheap alarm clock. But this ain't no coffee buzz. It's LIFE.