People's stories... Best part of my job

(The industrial area between Potrero Hill and Bernal Heights -– 11 a.m. on a Thursday morning in May 2007)

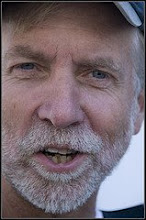

MY DISPATCHER sends me to the gate of a lumber yard just off Highway 101. A man leaning against the front wall sees me coming, rouses himself, and limps over to my taxi. “That’s the fastest cab I’ve ever had,” he says. “Barely 60 seconds!”

He is a forklift operator, headed over to the Mission District to visit the lumber company’s doctor.

“Three years ago another driver stacked a load of redwood two-by-fours all cock-eyed and they fell on me. Broke my ankle. I had one operation and then rehab, but it hasn’t been working out. He did some tests last week, and now I’m going back to hear the results. I think he’s gunna recommend me for retraining, but I’m 61 next month. What new kinda thing am I going to learn?”

I ask, “How long you been a forklift operator?”

“Thirteen. I was in the Army. A welder. Vietnam era, but I was always stateside. Utah mostly. Southern California for a while. Texas at the end. Almost got my twenty in -- that would have been all right.”

“My younger brother did twenty-three in the Coast Guard and retired with a nice pension just a couple years ago."

My fare says, “I gave it my best.”

“You’d just finally had enough?”

“Well,” he says, “it really wasn’t my choice.”

“They’d had enough of YOU?”

He allows a grim little snort. “It was kinda complicated.”

I say, “People’s stories are the best part of my job.”

“I was involved in an accident involving a fatality,” he says, “and everything sorta fell apart in my life for a while. Still hasn’t fallen back together, either.”

I briefly catch his eye in the mirror. “Someone you knew?”

“No. But I was ruled the responsible party.”

“Were you on duty?”

“No. It was a Friday night -- after work. Summertime. Still broad daylight. I’d had two beers. Really. Two beers. Left a little in the bottom of each of ‘em, too. Didn’t feel impaired in the slightest. My blood level was point-oh-nine [.09], and this was right after they lowered the limit from point-one-zero [.10] down to point-oh-eight [.08]. I was driving on a two-lane road a few miles outside of El Paso. There was a tow truck driving in front of me, and I couldn’t see around it. The guy ahead of the tow truck was driving a little red Volkswagen. Even the guy driving the tow truck testified that all three of us could have easily made it through the light. He told the court that the Volkswagen should have just kept going, should have just kept going straight on through the light. The limit was 65, and we weren’t even going the limit. Even the Texas Ranger said no one was speeding -- in fact he listed ‘lack of speed’ as a factor. But the instant this light goes yellow, the guy in the red Volkswagen hits his brakes. The guy in the tow truck, he's right behind him, he doesn’t have time to stop, so he jerks over to the right shoulder, and all the sudden there's this red Volkswagen stopped at a yellow light right in front of me. I’m going at least 50, probably maybe more. There’s oncoming traffic on my left -- I can’t go there. The tow truck is over to my right, throwing up dust and blocking the shoulder -- I can’t go there. I barely have a chance to hit the brakes before I impact the Volkswagen in the rear end.” He pauses. “And it just exploded…”

“Was he the fatality?” I ask.

“He was the fatality.”

“Man..." I say. "And they threw you out of the service because of it?”

“No, not exactly. The judge gave me six years, and this was around the time of all the base closings, and while I was in, all the facilities where I had worked closed down. When I came out I didn’t have anywhere to go where anybody knew my work. Plus, there’s all sorts of other people looking for work -- people who don’t have a felony.”

“Was it a long six years?”

“I served three, and then three years probation. The first three were in a work camp -- it wasn’t real hard time. Mostly they had us replacing fences along some pretty desolate stretches of highway. But it was better to be out working than sitting around the camp. We weren’t ever on real lockdown. It wasn’t really prison -- I can’t imagine a real prison. But I’d never been in any jail before, ever, and it was a shock. During probation I felt like running, just disappearing to some other state, but there was this one counselor who always knew what I was thinking and he kept talking me out of it.”

“Did you feel like you got a bad deal?”

He was slow to answer and, when he did, his voice was even, measured, as though he had long ago decided never to give anyone cause to think he might feel sorry for himself: “I thought there were a lot of reasons they could have found some other outcome for me.”

“Did they offer you a plea bargain?”

“No. They were trying to make examples out of people back then. They made an example out of me. The judge could have given me the most lenient option -- I was point-oh-nine [.09], not two-point-nine [2.9] or something. He had three levels of penalty he could choose from -- he gave me the middle level -- six years. He said I was a soldier, and I should have known better. I didn’t have a wife or kids, either -- I think that made it easier for him. If I’d had a family he mighta had to consider.”

“Musta been a torpedo in your life.”

“You’re telling me… You just can’t plan for something like that… Coulda happened to anyone, any time…”

While we’ve been talking, I’ve been maneuvering my cab in and out of traffic along a mile-long stretch of always-busy Cesar Chavez Street. And then another half-mile down Mission Street, every block thick with traffic, every crosswalk scrambled with pedestrians. I double-park in front of his doctor’s office, hit the meter, turn around, look at my fare, and ask him the question I’ve been saving: “Did it ever bother you that you were involved with a fatality? You know, having been at least a big factor in someone else’s death?”

“I’ll tell you..." He looks away from me, toward the shoppers on the sidewalk outside his window. I turn to my clipboard and busy myself recording the ride on my waybill. “I was sorry it happened. I couldn’t have been any sorrier. It really screwed up my life, but to tell you the truth it was hard to feel much for that guy. I’m really sorry he died -- that’s a fact -- but I didn’t know him. Didn’t know anything about him, never met him. He didn’t have any family, either. No one ever came to stick up for him, say what a great guy he was. No one came to cuss me for having run into him. I suppose the one thing I learned out of the whole deal is that you can kill someone easy -- real, real easy -- and not even mean it.”